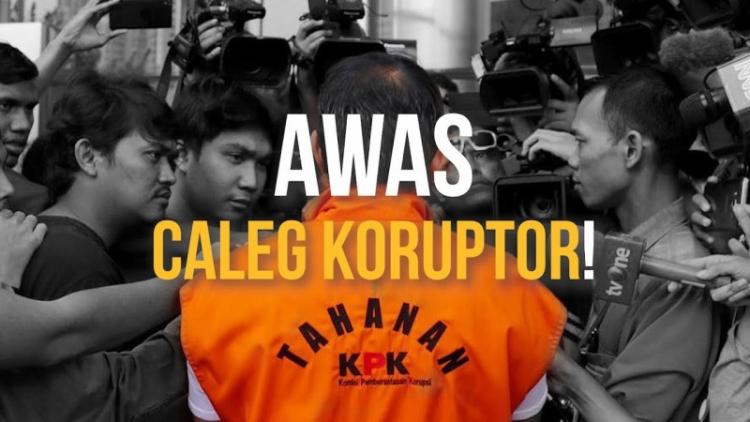

Beware of Former Corruption Convict Legislative Candidates

The Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) has released a list of 46 former corruption convicts who are registered as legislative candidates of the Provincial People's Representatives Council (DPRD) and the Regional Representatives Council (DPD) for the 2019-2024 period. This list has been updated through community input, from originally 38 identified candidates, later increasing to 40, and finally to 46 candidates identified as former corruption convicts. These are part of the 2,343 total candidates for the DPRD and DPD who are running in the 2019 elections, about whom the people need to be aware of their track record.

The former corruption convicts who are running for office come from 12 political parties namely Golkar, Gerindra, Hanura, Demokrat, PAN, Berkarya, Perindo, Garuda, PKPI, PBB, PKS, and PDI Perjuangan. Golkar is the political party that nominates the highest number of corruption convicts as candidates, with 8 candidates. PBB, PKS and PDI Perjuangan each nominates one corruption convict. Political parties that do not nominate former corruption convicts are PSI, Nasdem, PKB, and PPP. While PSI does not nominate former corruption convicts from the beginning, Nasdem, PKB and PPP had earlier nominated former corruption convicts, but later retracted their nomination.

The society is divided on whether former corruption convicts can run as candidates. For political party elites, they may run as candidates because there are no rules that prohibit them. The legal perspective is the basic argument for accepting those who have been corruption convicts to compete in legislative elections. However, in general the community does not agree if former corruption convicts run as candidates because morally, they have proven to be unfit to become public officials. At the same time, there are many other potential candidates who are untainted by corruption that the party could have offered.

The question is, with the high potential of money politics in the elections, don’t legislative candidates need large budgets, opening the opportunity to commit corruption when holding office? Data from the KPK stated that there were 178 corruption cases in 2018, with 91 cases involving legislative members. This shows that the high cost of becoming a member of the legislature is one of the main factors of corruption. The practice of mass corruption, such as that occuring in Malang, is a proof of the high political costs that must be borne by candidates.

The high cost can be calculated from socialization and political branding to the public, witness fees, printing of billboards, t-shirts, and others. Not to mention if it includes illegal practices such as money politics, and political dowry, in which cases the political costs will be more expensive. Based on a study by Prajna Research Indonesia, the minimum cost that must be spent by a candidate range from Rp 500 million to 2 billion.

In addition to the high cost of politics, the judicial review of the Supreme Court overturning the General Election Commission Regulation (PKPU) Number 30 of 2018 concerning the Nomination of Members of the DPR, Provincial, Regency and City DPRD, and PKPU Number 26 of 2018 concerning the Second Amendment to PKPU Number 14 of 2018 Regarding the Nomination of Members of the DPD, opens another opportunity for former corruption convicts to run as legislative candidates.

Then, how to suppress corruption in the legislative or political sector, especially in the context of the 2019 election? Regarding the decision of the Supreme Court allowing former corruption convicts to run as candidates, the KPU needs to be more active in informing the public about the track record of the candidates. Previously the KPU had proposed to display the profile of former corruption convict candidates at the polling stations (TPS). This is also a brilliant idea to prevent those who have been convicted in corruption cases from being elected as members of the DPR/D.

Meanwhile, in the medium and long terms, there needs to be reform of the political sector to reduce political costs through a series of agendas, including reforming the political party integrity system, strengthening transparency and accountability of political funds and election funds, and significantly increasing financial assistance from the state to political parties.

Indeed, there is no guarantee that candidates who are not previously convicted of corruption will not become corrupt when they take office. However, at least, by preventing the election of candidates who have a corrupt track record, the quality of Indonesian elections and democracy will be improved. *** (Dewi/Adnan)